Newspapers as a political tool: The Rowntree family and the problem of the Liberal Press

As part of our Rowntree Political Connections and Influences project, we wanted to undertake research exploring the Rowntrees’ ownership of newspapers in the early 20th century. We collaborated with the University of York’s Institute for Public Understanding of the Past to offer an internship to undertake this project. Charlotte Vallis completed this internship in the summer of 2025 and wrote this piece for our website based on her findings.

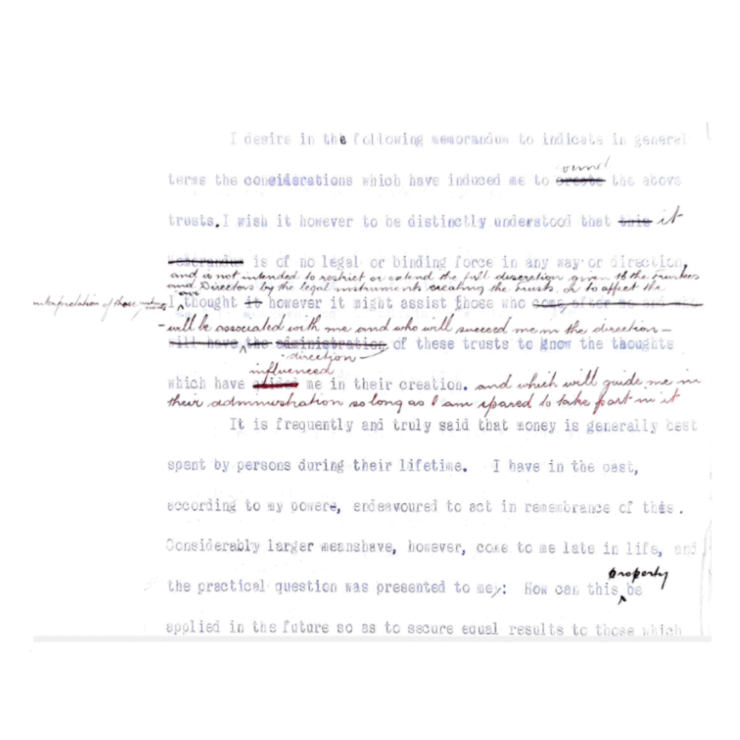

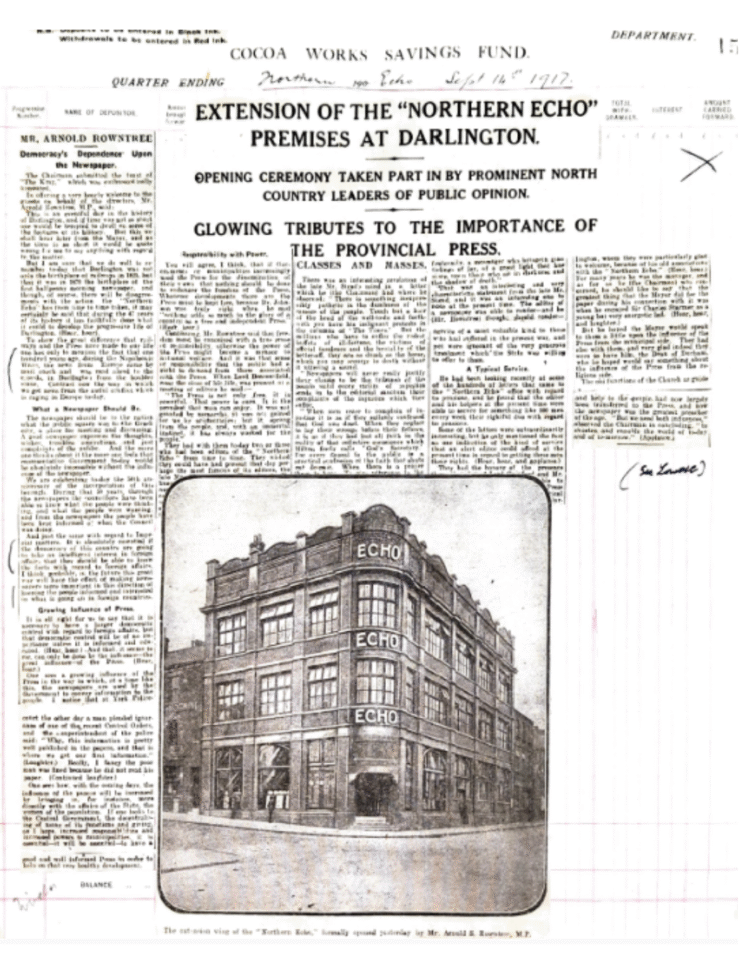

The Rowntree family are not widely known for their ownership of newspapers, but it forms an interesting chapter of the family’s political engagement. In 1903, Joseph Rowntree was convinced to purchase papers in Darlington, by Charles Starmer who was secretary of the Darlington Liberal Association.[2] The fear was that, although Darlington’s Northern Echo was running at a loss, if Rowntree didn’t step in, it would likely be bought up by a Conservative supporter and become part of the conservative “gutter press”.[3] This was the start of the Rowntree’s involvement in the provincial press and it came from the desire to strengthen the Liberal Party through the press. In 1904, Joseph Rowntree formed the Joseph Rowntree Social Services Trust (JRSST) to manage his growing newspaper interests. JRSST, now the Joseph Rowntree Reform Trust, was given a specific directive to focus on political aims, including managing the finances of the newspaper companies being purchased.[4] The quotation used in the title is from Joseph Rowntree’s memorandum on establishing the JRSST and makes clear his intent.

![]()

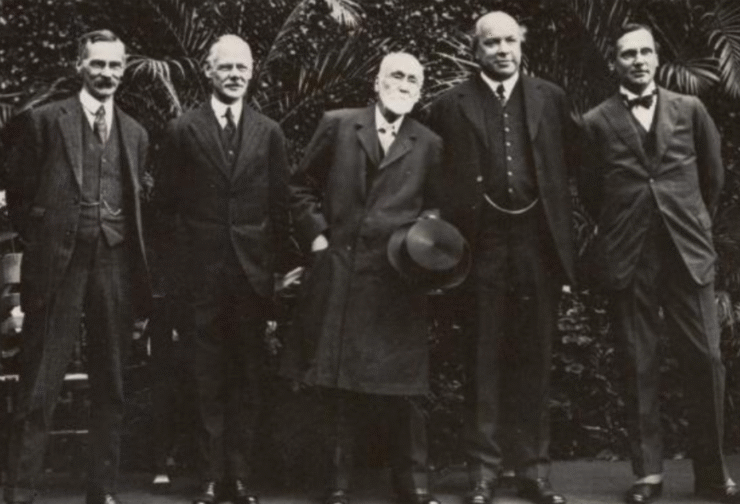

Arnold S. Rowntree, nephew of Joseph Rowntree, was appointed Director of this Trust. Known for his friendly and approachable character, “Chocolate Jumbo”, as the children of Bootham School and The Mount affectionately called him, worked advertising for the Chocolate Company.[5] This may well have been why he was given oversight for the newspaper sector. In addition, however, Arnold aspired to emulate Joseph Rowntree’s beliefs and actions in his work. In 1917 Arnold made a speech on the importance of newspapers for society. He echoed his uncle’s thoughts of a decade and a half before:

“A good newspaper expresses the thoughts, wishes, troubles, aspirations, and just complaints of the public… nothing should be done to endanger the freedom of the Press…because Dr Johnson was truly right when he said “nothing adds so much to the glory of a country as a free and independent Press.””[6]

Arnold took pride in this speech. In scrapbooks that focused on his career and wider works, two copies of this speech appear.[7]

Realistically, the Rowntree definition of “free and independent press” meant newspapers that were free to oppose the Conservative point of view more than anything else. Minutes of meetings of the JRSST continually praise newspapers where they have been perceived as helpful in supporting the Rowntree’s chosen political candidate.[8] The political aims of the newspapers sometimes came at the expense of the Rowntree’s other concerns: for example, an early scandal related to inclusion of betting information in their newspapers.[9]

Other issues quickly arose. Records show most of the Rowntree’s papers continually running at a loss. The Minute books regularly record requests for loans from the newspapers, which were typically granted and then written off.[10] This was only worsened by WW1, which led to a scarcity of paper and subsequent increases in running costs.[11] Furthermore, reading the Minute books, as time goes on, there is a growing sense that those who are leading the newspaper interests, Arnold Rowntree included, are increasingly overstretched by what newspapers required. In 1919, Seebohm Rowntree raised concerns about expanding size of newspaper interests, “in relation to the available time and the health of the three or four men bearing the main burden of the work”.[12] Almost two years later, Arnold Rowntree and J.B Morrell would echo the weight of the “heavy burden” of newspaper ownership.[13] At this same meeting, Lord Cowdray was mentioned for the first time. Cowdray ultimately established the Westminster Press, the company that took on the financial burden for most the Rowntree’s provincial papers by 1922, alleviating the pressure on Arnold and others.[14]

Nor would efforts in the national press prove straightforward. In 1907, the JRSST purchased the paper that would become The Nation. H. W. Massingham led the paper as editor until 1923. Massingham was “perhaps the ablest journalist of his time”.[15] Initially, Massingham’s appointment was greeted very positively amongst the Rowntrees and broader Liberal Press.[16] Massingham set high standards, holding weekly Nation Lunches, where he encouraged open discussion in order to create a more thoughtful range of ideas for the paper.[17] Arnold Rowntree was a regular attendee of these lunches when in London. In 1913, Arnold wrote to his wife that at a Nation lunch, he “was glad to find Massingham much happier than…expected”, highlighting the extent to which Massingham dominated the paper despite his encouragement of open discussion.[18] Under Massingham, The Nation was well-regarded: Ian Packer has described Massingham as successfully establishing “the house journal of the New Liberal intellectuals”.[19] Famous names were attracted to write in the paper: in October 1907, discussions were held on reimbursing Winston Churchill, and from 1913, “arrangements” were made to bring A. A. Milne to the paper.[20] However, Massingham continually ran The Nation at a loss, with the JRSST losing £50,332 throughout its time as owner.[21] Circulation remained small. This seemed to be manageable for a time, but other problems arose that meant financial concerns could no longer be ignored.

Although The Nation received significant funding from the JRSST and was technically under its control, Massingham very much viewed the paper as his. People recognised that, overall, the paper represented his views. Massingham was not afraid to court controversy: one of his employees at The Nation was H. W. Nevinson. Nevinson was also researching the issue of slavery on cocoa plantations, with Massingham’s encouragement, leading to a scandal for the Rowntrees and Cadburys.[22] Massingham personally challenged the Rowntree’s political views during WW1. In December 1916, Seebohm Rowntree raised new prime minister, David Lloyd George’s, concerns, that The Nation, a paper “owned by those friendly to him” was attacking him personally. Seebohm further said “things stated as fact by H. W. Massingham were not true” and that Seebohm was thus being put “in a false position”.[23] Seebohm, and the Rowntrees more widely, were supporters of Lloyd George. Seebohm’s frustration is evident. Arnold Rowntree, as peacemaker, replied to his complaint. He acknowledged Seebohm’s concerns, saying “he had already suggested to H.W.M the elimination of personalities from The Nation”.[24] Seebohm pushed the point and a resolution was taken to monitor Massingham and exclude personal attacks from The Nation, although policy criticisms were acceptable.[25] This became an ongoing concern.[26] At this stage, Massingham was moving away from supporting the Liberal Party and was becoming, instead a Labour supporter. His change in political focus coloured his attitude in the paper and undermined the original intent of the Rowntree’s.

Within a few years, the Rowntrees decided to sell The Nation. At the time, it was “widely regarded” that this decision came from Massingham’s continual criticisms of Lloyd George, although this was not entirely true.[27] On 3rd June 1921, Arnold raised concerns over the losses at the Nation, highlighting an anticipated loss for the year of £6,240. He felt “careful consideration” was needed regarding keeping the paper open. However, Joseph Rowntree intervened, saying “the Nation must be kept going at all costs.”[28] The resulting need for significant cost-cutting was communicated to Massingham by Arnold, but to little avail. Massingham would not take responsibility for the financial problems and things worsened throughout 1922.[29] In December, Massingham wrote to Arnold, offering his resignation. He referred to no financial concerns, instead giving his reasons for resignation as the “inevitable” re-election of Lloyd George, as well as Massingham being “tired of Editorship”. He then said that “Seebohm’s [opinion] may be quite right” on the direction for The Nation but that he couldn’t agree.[30] Massingham certainly emphasised political division as the main problem.

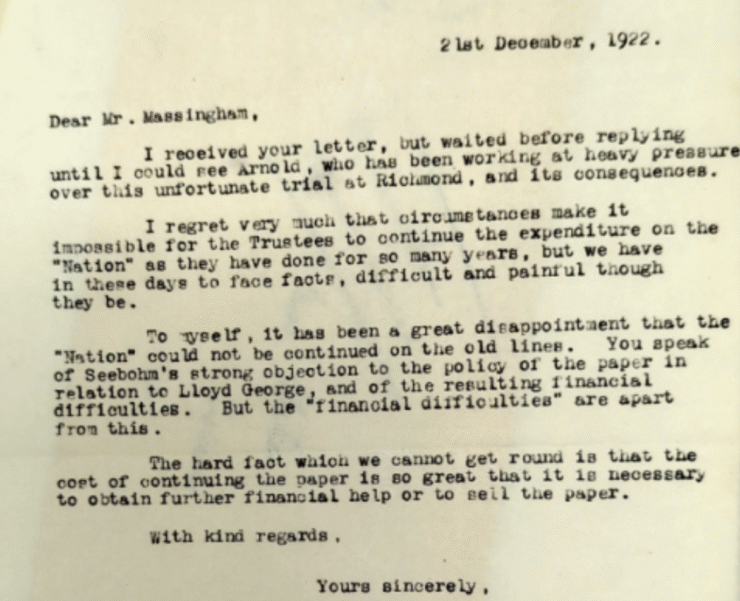

Although his resignation was duly accepted, Massingham attempted to backtrack when he discovered that overtures had been made to another Liberal group, the “Oxford Summer School Group”, to buy out the Nation, thus resolving financial issues.[31] Clearly concerned, Massingham then wrote to Joseph Rowntree, complaining of his mistreatment. Massingham felt that the only reason The Nation had financial problems was because the JRSST had stopped given it as much money because of “Seebohm’s strong objection to the policy of the paper in regard to Lloyd George”. Joseph Rowntree’s reply is clear:

To myself, it has been a great disappointment that the “Nation” could not be continued on the old lines. You speak of Seebohm’s strong objection to the policy of the paper in relation to Lloyd George, and of the resulting financial difficulties. But the “financial difficulties” are apart from this.[32]

By directing his complaint against Seebohm, Massingham pushed too far.

Massingham offered to try to raise capital to buy the paper himself throughout early 1923. However, by April he had failed to raise even half of the amount needed. He also had a heart-attack but would not acknowledge the limitations his health placed on his venture. Instead, he still complained of poor treatment, stating that “turnip-headed Arnold” was refusing to discuss matters fairly.[33] Ultimately, The Nation was sold as planned, the JRSST unable to justify absorbing the financial losses any further. Contemporaries believed Massingham’s version of events, that “the paper was sold over” his head and he was forced out for political reasons.[34] This belief was so widespread that Arnold was forced to write an official reply to the claims. In the late 1930s, the trust was still refuting the claim that Massingham was “forced out of his position…as has been stated in print by his son, the late H. W. Nevinson, and other writers.”[35]

Arnold’s official reply repeatedly cited financial reasons as being the main cause of the sale of The Nation, not political disagreements. If you consider that, much of the provincial press had been sold for the same reason, this does not seem an unfair claim on Arnold’s part. However, Massingham’s stubborn refusal to compromise his own political beliefs in running the newspaper had certainly created tensions that were difficult to overcome. For the Rowntrees, by the early 1920s, it was clear that newspapers were not the easily controlled political tool they had hoped for.

Charlotte Vallis Biography

Charlotte Vallis is a part-time PhD student at the University of York. Her own research focuses on Russia in the 18th century, particularly considering the confluence of gender and power. She completed an IPUP internship in Summer 2025 with The Rowntree Society for the Joseph Rowntree Centenary, exploring the Rowntree family’s newspaper ownership.

References

All images from originals held at the Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York

[1] Borthwick Institute of Archives: RFAM/BSR/JRF/9/1/1/20, “Memorandum on the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. The Joseph Rowntree Social Service Trust, Limited. The Joeph Rowntree Village Trust.”, Joseph Rowntree, 1904.

[2] Paul Gliddon, “The Political Importance of Provincial Newspapers, 1903-1945: The Rowntrees and the Liberal Press,” Twentieth Century British History, 14, 1 (2003): 27.

[3] David Cloke, Social Reformers and liberals: the Rowntrees and their legacy (Conference fringe meeting, March 2014), 42.

[4] Borthwick Institute of Archives: RFAM/BSR/JRF/9/1/1/20, “Memorandum on the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. The Joseph Rowntree Social Service Trust, Limited. The Joeph Rowntree Village Trust.”, Joseph Rowntree, 1904.

[5] The reference to Arnold’s nickname can be found in Elfrida Vipont, Arnold Rowntree A Life (University Press Aberdeen: Great Britain, 1956), p.51. However, this is an unreferenced work. In John Hick, John Hick An Autobiography (One World: USA, 2002) on p.19, a mention is made of “Chocolate Jumbo’s Strawberry Vit, a feast put on for us [Bootham School] at Rowntree’s chocolate factory by the head of the firm.” However, this does not directly name Arnold as Chocolate Jumbo. Bootham School were contacted for details from their magazine and confirmed a reference can be found in their July 1942 school magazine, 500-582.

[6] Borthwick Institute of Archives: RFAM/ASR/JRF/3/3, Northern Echo September 14th 1917, p.152.

[7] Both found in Borthwick Institute of Archives: RFAM/ASR/JRF/3/3.

[8] For example, Borthwick Institute of Archives: JRRT/2/1/1/1, Sheffield Independent Board Meeting, Dec. 1911

[9] Paul Gliddon, “Politics for Better or Worse: Political Nonconformity, the Gambling Dilemma and the North of England Newspaper Company, 1903-1914,” History, 87, 286 (2002): 227-244, accessed June 23rd, 2025, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24425638.

[10] Borthwick Institute of Archives: JRRT/2/1/1/1, First General Quarterly Meeting for 1906 Directors held at the Cocoa Works York, Wednesday Feb. 7th 1906, p.15.

[11] Borthwick Institute of Archives: JRRT/2/1/1/2, Meeting, November 8th 1920.

[12] Borthwick Institute of Archives: JRRT/2/1/1/2, Second Quarterly Meeting of the Directors of the Joseph Rowntree Social Service Trust Held at the Cocoa Works, York, June 3rd 1919, p.13.

[13] Borthwick Institute of Archives: JRRT/2/1/1/2, First Quarterly Meeting of the Directors of the Joseph Rowntree Social Service Trust Held at York on February 15/1921, p. 36.

[14] Ibid., p. 36; Borthwick Institute of Archives: RFAM/BSR/JRF/9/1/1/21, Memorandum on the Provincial Press, J. B. Morrell, 19.2.1942, pps. 1-9.

[15] Borthwick Institute of Archives: RFAM/BSR/JRF/9/1/1/21, Memorandum on the Provincial Press, J. B. Morrell, 19.2.1942, p.9.

[16] Alfred F. Havighurst, Radical Journalist: H. W. Massingham (1860-1924) (Alden & Mowbray: Oxford, 1974), 144.

[17] ibid., 151.

[18] Arnold Rowntree, “Letter to Mary Rowntree, 28th January 1913”, in The Letters of Arnold Stephenson Rowntree to Mary Katherine Rowntree, 1910-1918, edited by Ian Packer (Cambridge University Press: United Kingdom, 2002), 115.

[19] Ian Packer, “Religion and the New Liberalism: The Rowntree Family, Quakerism, and Social Reform,” Journal of British Studies, 42, 2 (2003): 252, accessed June 23rd, 2025, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/345607.

[20] Borthwick Institute of Archives: JRRT/2/1/1/1, Special Meeting of the Directors held on Monday 28th October 1907 at the Cocoa Works York, p.47; Borthwick Institute of Archives: JRRT/2/1/1/1, “The Nation”, p.190.

[21] Borthwick Institute of Archives: RFAM/BSR/JRF/9/1/1/21, Memorandum on the Provincial Press, J. B. Morrell, 19.2.1942, p.10.

[22] Lowell J. Satre, Chocolate on Trial: Slavery, Politics and the Ethics of Business, (Ohio University Press: USA, 2005), p.81.

[23] Borthwick Institute of Archives: JRRT/2/1/1/1, Special Meeting of the Directors held at the Cocoa Works York, 22nd December 1916, p. 241.

[24] ibid., 242.

[25] ibid., 242.

[26] ibid., 281.

[27] Havighurst, Radical Journalist, 293.

[28] Borthwick Institute of Archives: JRRT/2/1/1/2, Memorandum on the Present position of the Nation, 3rd June 1921, p.42-3.

[29] Havighurst, Radical Journalist, 295.

[30] Borthwick Institute for Archives: JRRT/2/1/1/1, H. W. Massingham, “Letter to Mr. Rowntree”, 10th December 1922, p.2.

[31] Havighurst, Radical Journalist, 297.

[32] Borthwick Institute of Archives: RFAM/JR/JRF/7/1, H. W. Massingham, “Letter to Joseph Rowntree”, December 16th 1922; Borthwick Institute of Archives: RFAM/JR/JRF/7/1, Joseph Rowntree, “Letter to H. W. Massingham”, December 21st 1922.

[33] Havighurst, Radical Journalist, 300.

[34] ibid., 301.

[35] Borthwick Institute of Archives: RFAM/BSR/JRF/9/1/1/21, A Review of the work of the J.R.S.S.T. 1905-1939 and suggestions regarding future policy, p.9.