Brynhild Benson: Star of the Cocoa Works Stage

This blog post has been researched and written by Catherine Hindson, Professor of Theatre History at the University of Bristol and a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. Her research focuses on how theatre helps us understand societies past, and incorporates topics including celebrity, heritage, ghosts, and well-being.

Histories of Britain’s early twentieth-century industrial landscape regularly position a group of benevolent, male factory leaders centre stage. The familiar family names of Cadbury, Rowntree, Lever, Hartley, Clarks shape our ideas about this heyday of British manufacturing. Without doubt these figures created, borrowed, and put in place progressive approaches to workplace recreation, education, and wellbeing. There are, however, other stories to be told, and amongst them are the stories of the women who shaped turn-of-the-century British industry.

Non-conformist beliefs – in particular the religiously-grounded business ethics adhered to by the Quaker Society of Friends – were a common factor amongst these new approaches to business, with the cocoa and chocolate makers Rowntree’s of York and Cadbury’s of Birmingham guiding the way. A second common factor can be discovered in the significant number of senior-level women who worked at the heart of Quaker-led companies. The stories of these employees – stories clearly visible in business records and factory publications (including works magazines) – have remained largely untold. We have much to learn about the role of women in industry leadership.

Quaker organisations shared a commitment to gender equality that was significantly greater than that of the wider world of work. While turn-of-the-century organisations have been both praised and critiqued for their paternalistic policies and structures, women regularly held responsibility for shaping and delivering factory culture, recreation, and education. It was their familiar presences that often represented day-to-day factory life and the sporting, learning and cultural opportunities it offered.

All who know Miss Benson (and who doesn’t)[1]

Brynhild Lucy Benson (1888-1974) was employed by Rowntree’s in November 1911; hired as a gymnastics instructor and based in the factory’s Social Department. She was the daughter of the well-known actor manager Frank Benson (1858-1939), whose company focused on productions of Shakespeare and who was central to the introduction to state school theatre trips as recognised educational activities. Her mother was Constance Fetherstonhaugh (1864-1946), a successful actress in her own right before marriage who continued to work on stage and screen as a wife and mother.

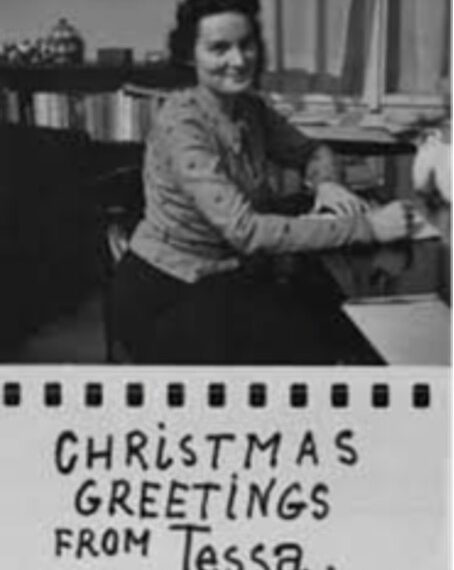

Brynhild Benson

From The University of Bristol Theatre Collection, MM/REF/PE/AC/217.

Frank Benson’s company aligned neatly with developing ideas around theatre, education, and wellbeing at Quaker-led companies. John Gielgud characterised it as ‘a kind of public school company: […] athletics, jokes, and no nonsense’.[2] An unidentified author of a 1958 press clipping remembered him as ‘impenitently what we should today label a “do-gooder”. Pa Benson’. Both Constance and Frank loved sports and exercise, and their two children ‘with their parentage […] quickly had to learn every kind of sport’.[3] Such descriptions and remembrances suggest how Benson’s theatrical company culture sat comfortably with factory culture and with the gradual reduction of anti-theatrical sentiment amongst the Friends that can be traced to the Quaker Renaissance and New Quakerism; shifts that were committed to, and driven in part, by Rowntree.

Brynhild Benson

(The Cocoa Works Magazine, 1911)

From originals held at the Borthwick Institute for Archives.

Brynhild Benson’s family connections would no doubt have supported her employment by the company, as would her Quaker heritage. Through her father’s line she was descended from the Rathbone family of Liverpool Quaker merchants, though evidence of key life events indicates that neither Frank nor Brynhild’s generations of the family actively practiced the faith. But nepotism was not a key reason for her employment. Brynhild Benson was more than qualified for the job. Affectionately known as Dick by her friends and family, she had spent little time with her theatrical touring family as a child. Educated at boarding school, she then headed to college at Dartford to train with Martine Bergman-Österberg (1849-1915). A forceful advocate of women’s emancipation in all areas of life, Bergman-Österberg saw her training of gymnastics and physical instructors as a key way to change women’s lives, granting them health, strength and confidence. Graduates of her college were highly sought after by industry leaders of the day.

After successfully completing her Dartford training, Brynhild Benson accepted a job as gymnastics instructor at the Reckitt’s factory in Hull in 1910. The firm produced cleaning and nutritional products, with its best-sellers at the time of Benson’s appointment Robin Starch and Brasso. Established in the 1840s, the company had grown considerably by the time Benson joined them and employed around 5,000 workers at their factory site. Benson stayed for just a year in this first job, but in this short period of time established a successful, growing gymnastics club for women, and led outdoor games, and Morris Dancing classes.

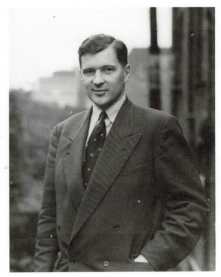

Miss Benson on gymnastics apparatus

With permission from The Österberg Collection

Reckitt’s works magazine published an account of Brynhild Benson’s leaving event that offers engaging details about her personality and her work-style. It records a thank you speech given one of her employees that ended: ‘No ordinary words could express what they felt at losing such a teacher as Miss Benson […] they had all learned to love her as a teacher, and believed she had learned to love them as pupils’. For ‘although Miss Benson had been only such a short time with them, her winning way had gained her the affection of everyone’. Benson’s response to their thanks and affection suggests the community that she created through the activities she led and hints at strong people skills. What she would remember most, she said, was ‘laughter’ and ‘laughter, she thought, was a great bond between people’.[4]

Brynhild left Reckitt’s for a job at Rowntree’s York factory. The culture she found there would have been familiar to her in many ways. Reckitt’s was also a Quaker-led firm; guided by the same tenets of integrity and prioritisation of recreation, welfare, and education as Rowntree’s. Employee numbers were slightly lower at the York cocoa factory at the time, but the firm’s Haxby Road site – opened just five years earlier – was state-of-the-art. Brynhild Benson followed the pattern of Rowntree’s hiring staff educated and trained at leading university colleges.[5] The Social Department might sound incidental to us today, but its staff team sat at the core of the business leading social activities and work at the organisation.

Although she had been hired for her qualifications as a graduate of the country’s leading gymnastics instructors training school, it is perhaps unsurprising, given her heritage, that she quickly became known for her involvement with the factory’s theatre. Reckitt’s had labelled her a ‘versatile instructress’ and we see that versatility throughout her short professional career. In addition to her own performances with the factory’s dramatic society, her contacts came in useful too for the organisation. Her celebrity father paid a visit to the factory in the following year, leading a session at the firm’s boys’ school.[6]

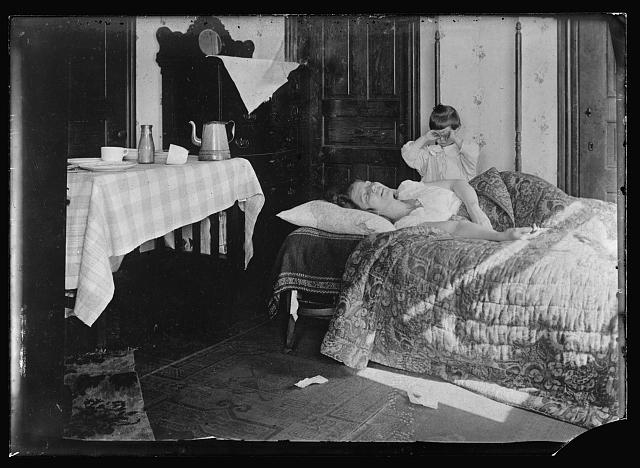

Miss Benson was to quickly become a star of the York cocoa works stage. Her April 1912 performance as Minnie Gilifillian in Arthur Wing Pinero’s three-act domestic comedy Sweet Lavender (a popular choice for dramatic groups across the country) was well-documented by the reviewer from the factory’s Cocoa Works Magazine. The role – the reviewer noted – ‘demands a degree of abandon rarely found in an amateur’, but Miss Benson ‘revelled in the part’. That this revelling also brought some disquiet and criticism from others in the dramatic society and audience is clear in what follows, for ‘we have heard it murmured that the part was overdone [and] at times too much attention was drawn away from the other actors’. Such complaints were met with scant patience by the magazine writer. ‘If that was so’, the reviewer concluded’, then other actors should have infused their parts with a relatively greater intensity’[7]

‘Sweet Lavender: Performances by the Works Dramatic Society’

Benson is on the back row, third from the left.

(The Cocoa Works magazine 1912).

From originals held at the Borthwick Institute for Archives.

A 1930 press clipping describes Brynhild Benson’s short industrial career as ‘strenuous social and athletic work among the women of big factories in the North of England’.[8] Ultimately it was to be a small chapter in her life; even in the most progressive of Quaker-led organisations, for women marriage meant resignation. Benson married in June 1917 and her career ended when she left Rowntree’s in May to prepare for her wedding. This was one of a number of limitations present for women staff members at the factory and within wider industry, and not all women’s experiences were the same: ‘class and occupational divides’ offered different levels of access to recreational and educational experiences during the decade that Benson worked at the factory.[9] Despite this, women employees like Brynhild Benson tell us more about the industrial culture of the early twentieth century, In her short time at the Haxby Road factory she modelled the firm’s priorities through both her delivery of physical education classes and societies and through her own active, very visible participation in Rowntree’s recreational schemes through factory theatre. The list of leaving gifts from departments across the factory are testament to the popularity and affection in which she was held.[10] Many other women worked alongside her – including the prominent figure of Miss Gulielma Harlock – who the next blog post on women at Rowntree will feature.

Miss Benson 1910

With permission from The Österberg Collection

Catherine Hindson Biography

Catherine Hindson is Professor of Theatre History at the University of Bristol and a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. Her research focuses on how theatre helps us understand societies past, and incorporates topics including celebrity, heritage, ghosts, and well-being. She is the author of three books, Theatre in the Chocolate Factory: Performance at Cadbury’s Bournville, 1900-1935 (2023), Female Performance Practices on the fin-de-siècle stages of London and Paris (2007), and London’s West End Actresses and the Origins of Celebrity Culture, 1880-1920 (2016). She is currently working on women leaders in early twentieth century industry and their connections with arts and creativity, and with the Rowntree Society, Port Sunlight Village Trust, and Unilever archives to share her research with wider communities.

References

[1]Cocoa Works Magazine, June 1916, p.1848

[2]Clipping, M&M Frank Benson File, University of Bristol Theatre Collection

[3]J. C. Trewin (1960) Benson and the Bensonians. London: Barrie and Rockliff, p. 121

[4]Reckitt’s Magazine Reference

[5]Catriona M. Parratt (2001) More than Mere Amusement: Working-Class Women’s Leisure in England. Boston: Northeastern University Press, p.206

[6]Cocoa Works Magazine, March 1912, p.1252-3

[7] Cocoa Works Magazine, March 1912, pp. 1250-2

[8]Clipping, M&M Frank Benson File, University of Bristol Theatre Collection

[9]Parratt, p. 210

[10]Cocoa Works Magazine, July 1917, p. 1954